Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin is a novel that contains a novel and, while not as obvious as Atwood’s approach, Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World felt like a similar experience by containing a character inside a character. That is to say Burden is a character inside Hustvedt, a fictional extension of her. The Blazing World reads like a sequel to The Shaking Woman through the lens of another character and on altogether a different topic that Hustvedt sets up so she could continue her study of the self. Parts of what she wrote in The Shaking Woman found their way into The Blazing World. Even the phrase “I remember” was put to use as if to illustrate its explanatory gains in a fictional setting. The Blazing World eschews the conventional relationship between characters and story to dive inside Burden in a way ordinary story formats can’t do. Hustvedt seems to be the reason why Burden exists and the latter the reason why the story exists, which in turn is the reason why readers pick up her book. So here then is a follow up to Shaking Woman, with Burden replacing Hustvedt as the lead character. To carry the weight of Hustvedt, the weight to replace a conventional story, Burden has to be larger than life on the inside, larger yet than Burden’s bizarre scheme with which she deceived the art world. But having already read The Shaking Woman, Burden’s inside reminded me too much of Hustvedt pondering about the self. And what Hustvedt was unable to say about the self in Shaking Woman, since after all that novel was about her illness, she could write about through Burden whose gender not illness establishes the source but not the limits of her discussion about the self. References to neurology, quantum physics, panpsychism and names such as Hegel, Anti Oedipus (which she hilariously refers to as Anti Octopus) form a compendium of views like puzzle pieces that don’t necessarily belong to the same picture. Confined by the medium of the novel, it was perhaps never Hustvedt’s intention to explain the self as she merely prompts readers to look outside the box. What isn’t novel-like is that, despite the life-like details of Burden’s inner life and the colorful characters that surround her external life, I hear in each of the character’s writings Hustvedt’s voice talking to me, probing questions she did not get to ask in Shaking Woman. Given that the story is about Burden’s artistic voice shining through the artwork of three male fronts, this effect might be intentional. The character of Bruno Kleinfield sounded more like himself, at least when he was first introduced, but the writings of most other characters bore the resemblance of Hustvedt’s contemplative voice in the words and tone of the craft she so masters.

Links

- Alva Noë: "Why Is Consciousness So Baffling?"

- Antonio Damasio: "The Quest to Understand Consciousness"

- Big Think: "Antonio Damasio & Siri Hustvedt"

- Big Think: "Daniel Dennett"

- californica: portrait of the artist as an organism (Jason Tougaw's blog)

- Daniel Dennett: "Cute, Sexy, Sweet, Funny"

- Emily Singer: "The Measured Life"

- Extraordinary People: The Boy Who Could See Without Eyes

- Gail Hornstein's Bibliography of "First Person Narratives of Madness in English"

- Gail Horstein, "The Hearing Voices Network"

- Gary Wolf on "The Quantified Self"

- Hearing the Voice Project

- Interview with Alva Noë (Salon)

- Jesse Prinz: "Waiting for the Self"

- Jill Bolte Taylor: "My Stroke of Insight"

- Koestenbaum on Viegener

- Maud Casey

- Rufus May: "Living Mindfully with Voices"

- Siri Hustvedt

- Tarnation Trailer

- The Quantified Self

- V.S. Ramachandran: "3 Clues to Understanding Your Brain"

- We Live in Public Trailer

Categories

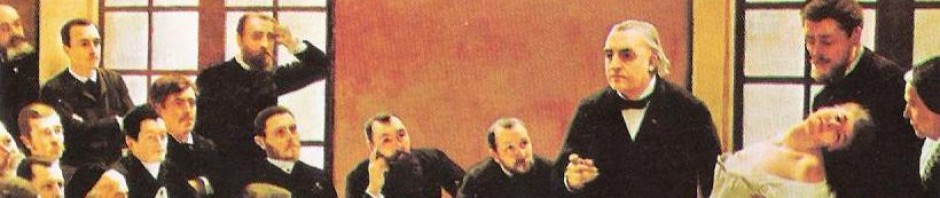

Berni, I agree that for anyone who’s already read The Shaking Woman, there’s a slightly recycled feeling to some of the neurological references in The Blazing World: Look, there’s Merleau-Ponty again! And Janet! And Charcot! And Husserl! Etc. The question, I guess, is whether this repurposing of Hustvedt’s earlier research serves a different enough purpose here to justify its inclusion. While at times I wished she’d used entirely new references — lord knows she’s got enough of them in reserve to draw from — my conclusion was that this novel wasn’t merely a fictionalized rehash of The Shaking Woman, so I’ll allow the repetitions.

I agree with you too that there’s a lot of Hustvedt in Harriet Burden (obviously), as well as in the measured, altogether shrink-like observations of Rachel Briefman, the similarly professional tones of editor I.V. Hess, and the intelligent but maybe inadequate daughterliness of Maisie Lord. And like you I noticed Bruno Kleinfeld’s voice as especially well-defined. But I don’t think he’s the only character who’s clearly differentiated from Hustvedt herself. Consider also the pretentious and privileged but not completely worthless Ethan Lord, the not-completely-a-California-New-Age-caricature Sweet Autumn Pinkney, and the superficially erudite and worldly Oswald Case, who may be based on a real art-world writer but immediately put me in mind of Graydon Carter. Phineas Q. Eldridge, too, although he shares a lot of Harriet Burden’s representational concerns, has a legitimately different persona from hers.

One characterization issue I did wonder about was the sexism of Case and the art dealer William Burridge, which struck me at times as too heavy-handed for plausibility: in the 21st century, aren’t these people supposed to undercut those they consider Other in more subtle, microagressive ways? Both of them also seemed amazingly provincial and naive about certain aspects of sex and art: Case seeming to believe that Rune’s womanizing precluded all possibility of same-sex desire or activity, Burridge apparently clueless (strategically ignorant?) about the intimate relationship that mental illness has historically had with artistic talent. But I’ve come out of the experience of reading this book with the suspicion that the art world is a subculture that needs to take frequent refuge from the innovation and rule-breaking it attempts to traffic in, in the form of amazingly retrograde and philistine behavior –so it may be that Hustvedt is alarmingly right on in her depictions of these people.