As a lit person by background, I found Hustvedt’s book to be just the sort of thing I got into liberal studies to read: nonliterary material (albeit, in this case, material with plenty of literary implications) rendered with a literary sensibility. Hustvedt brings to her task not only a literary eye, a literary prose style and the ability to call up pertinent references to writers from Emily Dickinson to Borges to Rimbaud; she also brings literary values, including respect for readability and narrative, interest in the personal character and backstories of the doctors and patients she writes about, and an understanding of human emotion in its complexity and contradictoriness (and this isn’t a reference to her mirror-touch synesthesia). Since I value these things too, I’m predisposed to trust Hustvedt’s motives and therefore, probably, her findings.

It’s worth noting, though, that Hustvedt is not only a fiction (i.e., imaginative) writer; she is also a scholar and researcher. While the skill sets for those activities can overlap with that of a novelist, they’re not equivalent. Literary history shows that you certainly don’t need a PhD in literature to write good novels, but Hustvedt nevertheless has one, and you can’t earn a PhD (as opposed to, for instance, an MFA) without well-developed research skills. Rita Charon, the MD and literature PhD whose efforts to legitimize storytelling in medicine Hustvedt mentions in the text, and whom she names in the acknowledgements as a major impetus for her beginning the book in the first place, is an interesting parallel case. (I was, incidentally, surprised to read that Charon’s Program in Narrative Medicine is housed at Columbia University, an institution whose support for interdisciplinary work in general is sufficiently grudging that it doesn’t offer doctoral programs even in such established interdisciplinary fields as American studies, African-American studies and women’s studies.)

It’s clear from The Shaking Woman that Hustvedt hasn’t relinquished the research habit since graduate school: not only does extensive research seem to be a standard part of her novel-writing process, she appears to relish research in and for itself. I noticed, too, in looking over her biography, that her undergraduate major was history rather than literature. She clearly has retained that interest in history, along with a general thirst for extraliterary knowledge of all kinds. All of the above is to say that whatever she’s writing about, Hustvedt is likely to bring to the table a more interdisciplinary stance than many novelists would.

Hustvedt actually brings up the topic of interdisciplinarity herself at one point in the book. Though she’s talking specifically about the dangers of specialization and disciplinary isolation in the sciences, her observations also apply to the humanities and get at the pros and cons of a course/program like the one we’re in:

The issue here is one of perception and its frames, disciplinary windows that narrow the view. Without categories, we can’t make sense of anything. Science has to control and restrict its windows or it will discover nothing. At the same time, it needs guiding thoughts and interpretation or its findings will be meaningless. But when researchers are trapped in preordained frames that allow little air in or out, imaginative science is smothered. (p. 79)

And an earlier comment of Hustvedt’s suggests that scientists need to be at least interdisciplinary enough to admit the history of medicine into their training:

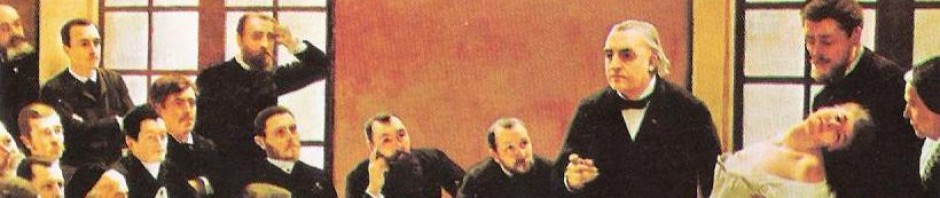

Medical history changes, and many if not most doctors have little grasp of what came before their own contemporary frames for diagnosis. They are incapable of drawing parallels with the past. (p. 75)

One obstacle interdisciplinary scholars often have to contend with is the perception that they’re dilettantes without deep knowledge of any one field. With The Shaking Woman, Hustvedt seems to have escaped this fate: the book’s front cover blurb (for the Picador edition) and the majority of its back cover blurbs are provided by scientists, not literary critics. Mark Solms, whose work she cites in the book, is even quoted as saying that Hustvedt “displays greater understanding of the underlying philosophical and historical issues that are at stake in this field than is displayed by many of my colleagues” (though not, significantly, the scientific issues). I’m not sure acceptance by scientists was Hustvedt’s primary goal in writing The Shaking Woman, but it’s interesting to consider what it is about this book that has made it so apparently successful in crossing disciplinary boundaries.

Mark Solms wrote a really interesting book entitled The Brain and the Inner World, which is all about finding ways to bridge gaps between neuroscience and psychoanalysis–very much the kind of interdisciplinary work you’re talking about here. Also: He owns a winery in South Africa that is also an archaeological site. He’s a fascinating guy–and a friend of Hustvedt’s.

Hi Liz,

Your comments on the interdisciplinary approach in Hustvedt’s book is helpful in that they summarize the different disciplines she combined to write her book, something she did not bother to explain to her readers. Of course the very content of her book lends itself to this sort of fragmented yet unified approach. Without warning, she lets out a stream of thoughts that later on make sense not by the way her narrative is structured but by how it shapes our experience in 1reading the book. After all, isn’t reading another person’s thoughts not a way to know that person, its self, and isn’t this book not about Siri Hustvedt, her self? In having the structure of her narrative mimic the structure of her thoughts, it appears that most of us in our daily activities do not think along a single isolated thought from start to finish, as when we try to solve a mathematical problem, but rather we follow a stream of thoughts. And this stream of thoughts is closest to how we know our mind operates when we’re being ourselves.

It is also worth noting that the interdisciplinary approach seems not only to be an effort to mimic a drifting, fragmented mind but contrary to that, it might be an effort to understand a unified mind, the notion that one’s self is to be found outside of one’s self. As you said, scientists provide the majority of the back cover blurb, indicating not only the scholarly research that went into writing this book but also the interdisciplinary root of asking a question as profound as Hustvedt’s.