1. What characteristics or elements, in your opinion, does a work need to display in order to be categorized as a novel? Does The Man Who Walked Away — a fictionalized characterization of two real-life historical figures whose plot is, by conventional definitions, slight and whose chief narrative conflict is between a man and his own condition rather than any external character or force — meet that definition? Are there other categories or descriptions (prose poem? imaginary history? therapeutic fantasy?) into which Casey’s book might fit at least as well as that of novel?

2. We’ve now read two texts written by novelists: Hustvedt’s selective “history” (her own term) of medical and philosophical developments that might provide insight into her own condition, and a fiction by Casey about a different real-life sufferer that (in my view) sits a little uncomfortably in the category of novel. If we assume that Hustvedt and Casey’s texts share the goals of shedding light on particular body/mind conditions and of writing in a literary style, which text do you think is more successful in meeting those goals? Is the fact that the condition Hustvedt writes about is her own a freeing or limiting circumstance?

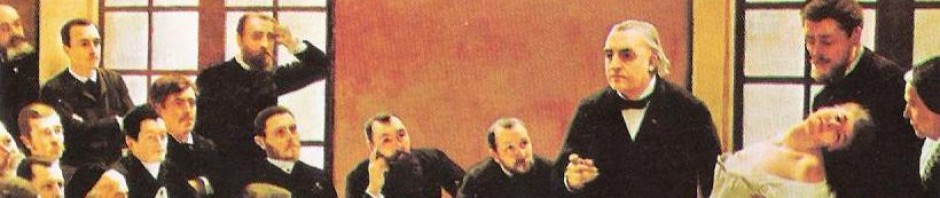

3. Ian Hacking suggests that transient mental illnesses need to meet four conditions (or vectors, as Hacking calls them) in order to occupy “ecological niches” and thus establish themselves during a particular cultural moment: diagnosability/classifiability, cultural polarity (i.e., occupying a place between culturally approved and culturally reviled behaviors), observability, and the provision of “some release that is not available elsewhere in the culture in which it thrives.” Both Hacking and Casey attempt to give some idea of the personal losses and traumas from which Albert Dadas might have sought release through his compulsive traveling, but these factors are too individual to provide a general motivation for the many fugueurs who became medically visible in the wake of Dadas’ diagnosis. Hacking may provide an important clue about this larger group when he writes, “The fugueur was not from the middle classes. But he was urban or had a trade. There are almost no reports of peasant or farmer fugueurs.” What release might compulsive traveling have offered for this class of people at this moment in history?

4. Both Hacking and Casey mention that Dadas fell out of a tree at age eight, and Hacking raises the possibility that Dadas sustained a head injury at that time that may have played a role in his compulsive traveling later. Beyond this, though, neither writer provides an answer to the question of whether Dadas’ condition (and that of fugueurs more generally) had any biological/neurological basis or was more purely a psychological/cultural condition. Based on what Damasio and Noë have written about the brain’s role in conscious experience and behavior, including its interactivity with its environment, how do you think they might begin to explain Dadas’ case and the larger phenomenon of late 19th-century fugueurs? Would they have considered the fugueurs ill in a biological sense?